Since literature is unimaginable and inconceivable outside the concept of language, the issue of language is central to the discussion of African literature. The ideological disparity on the language of African literature that has persisted till the present day was issued during the Makere conference.

In determining the identity markers of an African work the role of language was interrogated. It felt logical to conclude that the literature of a people and the language of the people should be inherently connected.

The use of English language was not just seen as a continued form of psychological subjugation it was accused of elitism, excluding the very people the works should be written for. This line of thought was reinforced when Christopher Okigbo displayed intellectual arrogance by saying, “I do not read my poem to non-poets” while speaking to Bernard Fonlon.

How can a literature improve the condition of a society if it does not reach the people of that society, where does that leave the attribute of functionality peculiar to African expression?

Ngugi wa Thiongo was one of the strongest advocates of what I’ve termed the “returnee model”. This model ridiculed the idea that “African” could be forged from the very same structure that sort to undermine the humanity of Africans i.e, colonialism and its extension including the English Language, they sort rather to return to an expressive state that existed prior to the influence of Europeans.

A direct derivation of content and mode from oral tradition that was unarguably steeped in indigenous language was proposed. Ngugi’s criticism centers on the devastating role the language played in the colonisation process. In his later works he would give more insight to his view on the issue of language.

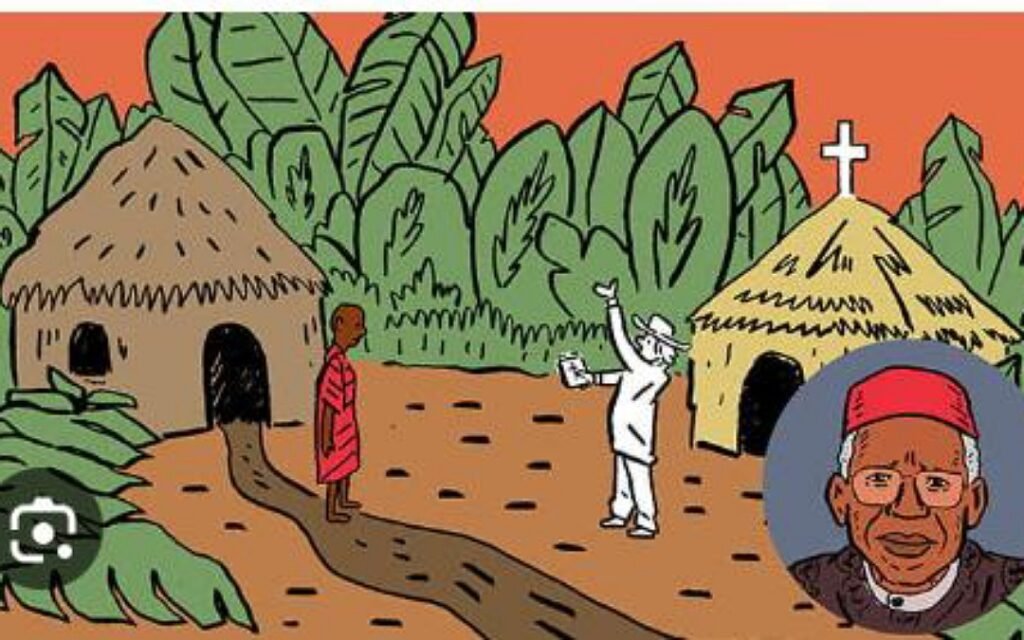

In Decolonizing the Mind he states that, “the bullet was the means of physical subjugation while language was the means of psychological subjugation”. Furthering this view of language as the harbinger of neo-colonialism, he added that, ” the continued use of the English language means imperialism continues to press gang the African hand to plough to turn the soil over, putting blinkers on him to make him view the path ahead only as determined for him by the master armed with a bible and sword.

Triggered by the output of this conference, Obi Wali published his essay, “the Dead End of African Literature” a year later. He threw more insight at the literary proceedings of the event.

It was through his publication we learn that Ulli Bier while discussing the poetry of J.P Clark during the congress, extolled the evident influence of T.S. Elliot and Hopkins. He also made mention of Una Maclean’s review of “song of the goat” and sites the opening remark, “the author of this poetic melodrama possibly perceives himself as some sort of Tennessee Williams of the Tropics”.

He cited some more examples and came to the conclusion that, “African literature as now understood and practiced is merely a minor appendage in the main stream of European literature”. This argument aligns with John Povey point of view, he stated that, “when one can so readily make cross-comparisons with the work of Achebe and say, Thomas Hardy or Joseph Conrad, one has the satisfying sense that the African writer can be conveniently set within the context of the much wider field of English language writing” (1972, 97).

Obi Wali expressed his disappointment at the current trend of literary expression especially with the seeming defeat of Negritude and Amos Tutuola school of African writing, that took place during the conference. For Wali, the use of European language rather than foster the mental development of Africans and their literature poses a dead end.

It only leads to sterility as there is a limit to what a language not steeped in a nation’s consciousness can convey. He concluded his argument by stating, “until these writers and their Western midwives accept the fact that any true African literature must be written in African languages, they would be merely pursuing a dead end which can only lead to sterility uncreativity and frustration” (1963, 20).

This returnee model did not end with that conference or that decade. It spurred disciples that would continue to preach years later against the perceived ills of using the English Language. Ashcroft et al (1989), one of the offshoot of this school of thought reiterates the concern of this model by stating that, language during the colonial times was the medium through which hierarchical structure of power were perpetuated and the medium through which conceptions of truth, reality and order were established, control over language became the main feature of imperial oppression.

Some intellectuals like Christopher Okigbo, Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe took a polar position on the language debate. To them, while language is an important factor the totality of literature goes beyond its language of expression.

A definition of African literature that focuses on language alone would be limiting since human experience forms the basis of literature and language is just a vehicle used to carry the experience home.

Chinua Achebe spoke in favour of the English language. Udofia states that he has said, “let us give the devil his due” colonialism gave Africans a language with which to talk to one another. The unifying element of the language cannot be ignored, it brings to mind the question, “what language was the conference being held in”?

The essence of writing is to communicate and if indigenous languages poses a barrier to communicating to the audience an author has in mind, then the English language should be allowed to fulfil that purpose. Achebe suggests, writers expands the frontier of the language to convey their sensibilities as Africans.

He recognizes the importance of ethnic literature but makes a distinction between this and national literature, they’re separate but equally important aspects of African literature and ought to grow side-by-side. What Chinua Achebe calls for is the expression of “orality” in African texts.

Orality as evident in traditional African discourse through the use of proverbs and aphorisms which channel communication in Africa culture should provide a “formulaic” framework for speech acts, discursive modes and the structure of thought in these newly written texts.

A textualized orality is often possible when the African novels are structured like the traditional narrative, possessing such intrinsic properties (character type, narrative function, rhetorical devices as well as the role of metaphor and symbolism). If these properties have had a marked effect on the conception and execution of a text then we can say such a text carries the weight of the African expression.

Achebe has been able to achieve this in his text “Things Fall Apart” that is now considered an African classic. Achebe believes the African writer can strive to fashion out an English language that holds the burden of his peculiar experience while maintaining a degree of universality.

Wole Soyinka on the other hand proposed an alternative Pan-African language. A language that functions like the English language but originates from Africa. While this would have conferred a distinct identity, it was highly infeasible.

Africa is a vast continent, consisting of more than fifty nations and several hundred languages and ethnic groups. To formulate and then integrate a language that would meet the needs of this vast nation was unlikely. Nigeria is yet to succeed with its WaZoBia project and it doesn’t even make up for half the continental diversity.

Literature as has been said by multiple critic does not exist in a vacuum, the language of conveyance follows the same rule. The contact between Africans and Europeans is not one that can or should be dismissed and a fusion of this historical experience cannot result in a creative endeavour that solely maintains the hierarchy of indigenous language.

This is more so when we consider the fact that the access these writers had to literacy was through the English language. The tradition of “writtenness” is largely woven around the English language in African societies. In other words, the language is a bi product of the same process that popularized the writing (that writers are arguing about) and the same process that made the new nation-state of Africa (which they are trying to define).

African writers cannot speak about colonial and post colonial, make reference to it in their writing and then try to ignore the language that rode on the back of colonialism. In discussing the language issues, it should be recognized that formal education is eurocentric and this is what predates the written.

If indigenous languages were used to convey creative expression, how many Africans would be able to access it? Those who are confined to the use of their native languages are they literate in those indigenous languages? It appears that this method would even draw a larger barrier between literature and the masses.

Modern African literature in European language is an effort to reintegrate a discontinuity of experience in a new consciousness and imagination. It is evident that works written in European language are formally related to the Western tradition of written fiction not only by recourse to the language of the colonizers and the range of formal resources it offered, but also by the colonized experience itself _ constituting in all its comprehensive scope, political, socio-economic and cultural _ the new context of life which Africans existence came to be enclosed.

This is the reality of Africans, to reject it or to pretend it isn’t portends a disastrous disillusionment and an irrecoverable loss social awareness.

Conclusively, it is better for an African writer to think and feel in his own language and then look for an English transliteration approximating the original.

An African writer draws upon dual heritage to convey expression. Transposition, transliteration or translation thus assumes the most viable solution to the language problem.

In discussing the language controversy, African literature corpus is in fact multilingual. The variety of languages covered by the term can be appreciated by a consideration of the range of literatures in Africa

What is African Literature?

The dismissal of language as a determiner leaves us still with the question, what is African literature? How can we identify African literature if not through language and no definitive marker? Christopher Okigbo during this conference shared a personal story of identification, he was able to identify the difference in nationality of a guitar player based on how the guitar was played, he concluded that, “African writers have adopted English much as the musicians have adopted the guitar, and if they really spring from African soil, if they’re kneaded and leavened by African experience their manner, their expression will bear an African imprint whatever their theme may be”.

Through this statement Okigbo leaves thematics without restriction while placing specifications on “experience”. It remains then that there is an African sensibility that can be sensed in a work without prior definition. What is African literature is a question that can have multiple answers attributed to it, there has been no census and what it means for one critic can differ for another.

Modern African literature is a conglomeration of many variables. It relies on the fusion of language, setting, authorship, sensibility, experience and even audience. It can thus be defined as, a written work of art by an African, steeped in African conscious and expressed in either indigenous or colonial language

tailored primarily for an African audience.